^

— LINKS

— Landscape

in the Jura (1864, 72x91cm; 3/20 size, 51kb _

ZOOM

to 3/10 size, 180kb _ ZOOM++

to 3/5 size, 681kb)

— Le bois

aux biches au bord du ruisseau de Plaisir-Fontaine

(1866, 174x209cm; 838x1007pix, 151kb _ ZOOM

to 1676x2012pix, 376kb)

—

Chute

d'Eau (823x1255pix, 102kb)

—

Chute

d'Eau (823x1255pix, 102kb)

— La

Vague (774x1097pix, 177kb)

— Vagues

(985x1229pix, 110kb)

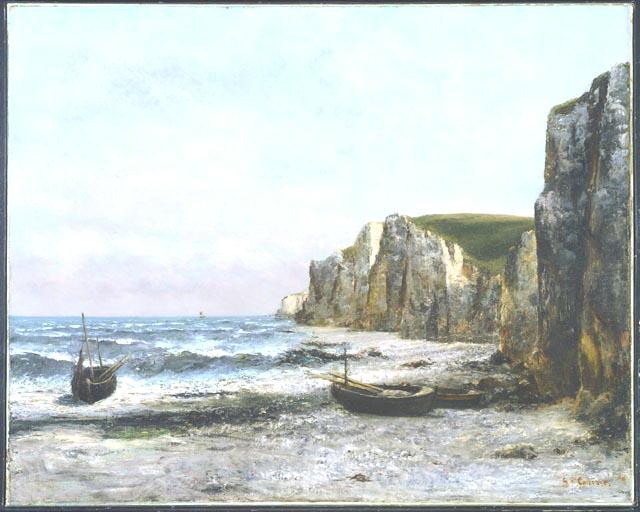

— Les

Falaises d'Étretat (721x900pix, 55kb)

— Bords

de la Seine (809x973pix, 45kb)

— Enterrement

à Ornans (1850, 314x663cm; 800x1752pix, 134kb

_

ZOOM to 1400x3076pix, 1040kb)

— Cribleuses

de blé (772x1068pix, 100kb _ ZOOM

to 1400x1784pix, 624kb)

— Le

studio de l'artiste - Allégorie réelle: occupant sept ans

de ma vie artistique et morale (1855; 682x1169pix,

152kb _ ZOOM

to 1400x2411pix, 879kb)

— Bonjour,

Monsieur Courbet aka La Rencontre (1854;

958x1080pix, 84kb _ ZOOM

to 1400x1591pix, 645kb) _ Out on his way to some plein air painting, Courbet

meets the art philanthropist Alfred Bruyas and his servant.)

— Alfred

Bruyas (1853; 600x469pix, 88kb _ ZOOM

to 1400x1095pix, 328kb)

— Courbet

au Chien Noir (832x1100pix, 64kb _ ZOOM

to 1683x1400pix, 615kb)

— Self~Portrait

(43x35cm; half-size, 72kb _ ZOOM

to full size, 263kb) (you may want to increase the brightness of

your screen for this one)

— Self-Portrait

(Man with a Pipe) (1849)

— Château

d'Ornans (1855, 82x117cm; quarter-size; 826x1186pix, 619kb _ ZOOM

to half-size 1653x2393pix, 2810kb) _ The country around Courbet's

native town of Ornans, in eastern France, inspired most of his paintings.

Like his contemporaries who worked near Barbizon, Courbet revitalized

the landscape tradition with views of distinctive regional features observed

at first hand. The town of Ornans appears in the valley below.

— Portrait

of the Artist's Sister (32x25cm; full size)

— Juliette

Courbet (1844; 1400x1159pix, 462kb)

— The

Young Ladies of the Village (1852) — The

Sleeping Spinner (1853)

— The

Fox in the Snow (1860)

— Beach

Scene, (1874, 38x55cm) _ Painted later in life than many of his beach

scenes, this picture of the shores of Lake Geneva was made when Courbet

was in exile in Switzerland. Its composition refers back to the ‘sea landscapes’

he painted in the 1860s, although here one small figure appears on the

shore. Courbet uses minimal colors to convey the mood and the natural

elements, while the style of this work is more refined than his previous

paintings of similar subjects.

— Low

Tide at Trouville, (1865, 60x73cm) _ This is a particularly harmonious

painting in terms of color and mood. It was painted during Courbet’s 1865

trip to Trouville, and shows the artist experimenting with ways of creating

depth on a two-dimensional surface. The salmon-pink horizon constitutes

over a third of the painting, dissolving into softer pinks, grey and blue

for the sky and to browner tones for the beach. At this stage in his career

Courbet was very much influenced by Whistler, whose seascapes show great

attention to the blending of color.

— The

Wave (1871, 46x55cm) _ Although Courbet would have observed waves

breaking, it is obviously inconceivable for any painter to sketch or paint

one particular wave. Its motion, although repetitive, is never identical,

and (until the development of snapshot photography) impossible to capture.

A wave represents one moment in time – here in thickly laid-on paint,

the crest of the wave curls over and crashes towards the front of the

painting. This creates a sense of immediacy for the viewer, as if we are

witnessing the wave spilling towards us.

— L'Eternité

(1865, 65x79cm) _ This intense and melancholy painting is painted over

a dark ground (or underlayer) which explains its somber tone; as Courbet

himself said: ‘Nature without the sun is also dark and black. I do as

the light does, I illuminate the parts that project and the picture is

done’. The title draws our attention to the vast expanse of sea and sky,

its timelessness and our own relative inconsequence.

— Le

Pont d'Ambrussum (1857; 600x809pix _ ZOOM

to 1400x1888pix, 970kb)

— Le

Repas de Chasse aka L'Hallali du Chevreuil (1858; 600x945pix

_ ZOOM

to 1400x2206pix, 1711kb)

— Pêcheur

au bord de la Loue

— Portrait

of the Artist, called "The Wounded Man" (1854 _ ZOOM)

— The

Cellist, Self-Portrait (1847)

— Portrait

of the Artist (Man with a Pipe) (1849)

— The

Bathers (1853) — The

Sleeping Spinner (1853)

— The

Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (Summer) (1857; _ ZOOM)

— The

Oak at Flagey (The Oak of Vercingétorix) (1864) — The

Source of the Loue (1864)

— Jo,

the Beautiful Irish Girl (1865) — Seacoast

(1865)

— The

Sleepers, or Sleep (1866)

— Woman

with a Parrot (1866)

— The real, abstract, clean, honest L'Origine

du monde (2004; 450x600pix, 116kb _ ZOOM

to 1050x1400pix, 1264kb) by “Eva Tsug-Tebrouk” replaces Courbet's

X-rated misnamed L'Origine du monde (1866) because this is a

site that avoids anything that might be considered unsuitable for children,

though young children are more likely to be disgusted rather than harmed

by such pictures, which are more unsuitable for adult men, and most unsuitable

for teenaged boys. Courbet's painting is deceptively named, as it does

not show the origin of the world, but, presumably with the intention of

shocking, features prominently the (very hairy in this case) anatomical

part out of which a human comes out at birth.

— Count

de Choiseul's Greyhounds (1866) — The

Woman in the Waves (1866)

— The

Source (1868) — The

Cliff at Etretat after the Storm (1869)

— Still

Life with Apples and Pomegranate (1872)

— Still

Life: Fruit (1872) — The

Trout (1872)

— Woman

in a Podoscaphe (1865; 911x1103pix, 146kb)

— P.-J.

Proudhon en 1853 with two young girls, one drawing, one playing (1865;

818x1105pix, 164kb)

— Pierre-Joseph

Proudhon alone (1865; 1128x892pix)

— The

Beach at Trouville at Low Tide (1865; 761x1026pix)

— The

Beach at Trouville at High Tide (1865; 791x1127pix)

— Deer

in the Snow (1867; 890x1108pix)

— Dear

Taking Shelter from the Winter Snow (1866; 831x1129pix, 350kb)

— 133

images at Webshots

— 230

images at Bildindex