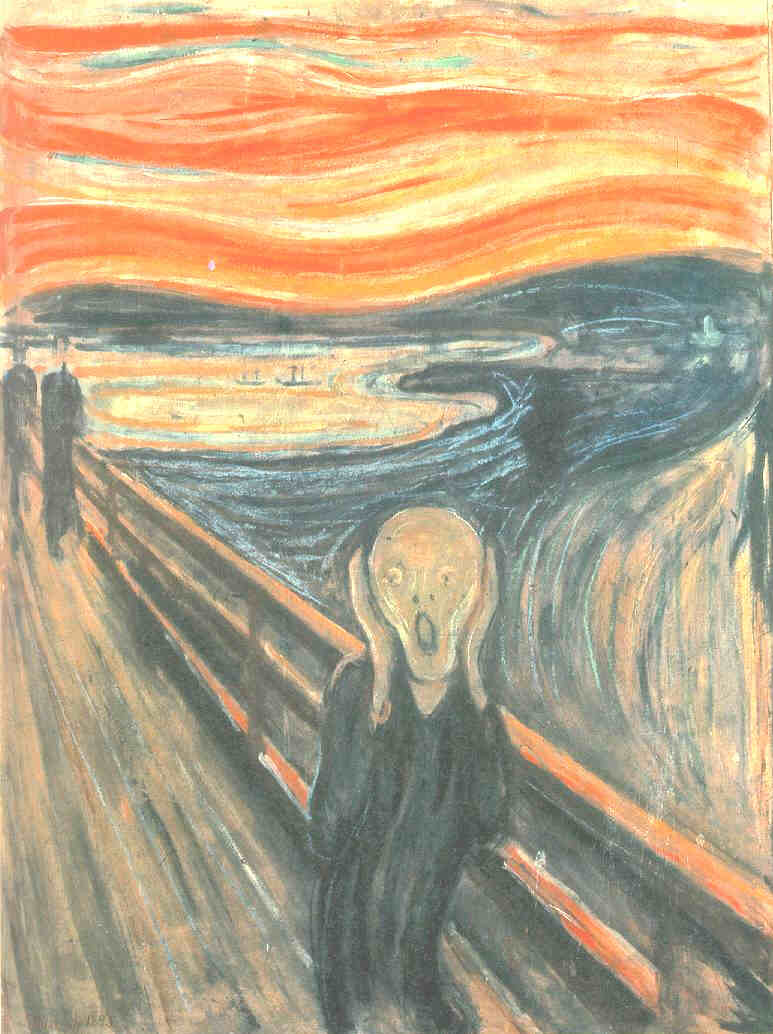

THE SCREAM

by Edvard Munch

| ABOUT

THE ARTIST ^top^

An anxiety haunts the work of Edvard Munch, that is expressed with a formal inventiveness that impinges upon the emotions before we are even aware of the subject; the deeper regions of the psyche are accessible only through the potent agency of rhythm and color. When Munch began studying art in Christiania (now Oslo), Norwegian artists practiced a form of Protestant, populist realism. Munch was, however, from the very start, an innovator. True, he painted genre scenes, but in a spirit all his own. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was five. At fourteen, he watched his fifteen-year-old sister Sophie succumb to the same disease. When, at twenty-two, he acquired the technical means to portray it, her death became an obsession to which he returned again and again: the wan face in profile against the pillow, the despairing mother at the bedside, the muted light, the tousled hair, the useless glass of water. Norway had long been under the influence of German aesthetics. Until 1870, Norwegian artists usually went to Dόsseldorf to study and pursue a career. Later, they went to Paris, Berlin, Munich and Karlsruhe. But by 1880, Paris had become the center. And so it was that Munch, in 1885, undertaking his first journey at twenty-two, was led to discover French art and the Symbolist spirit. It was in these circumstances that Munch's personal neurosis, the anxiety which women caused him (although he pursued them incessantly until the great psychological crisis of his forties), entered the ambit of cultural anxiety expressed in Symbolist art. Munch was chiefly concerned with his own existential drama: 'My art', he declared, 'is rooted in a single reflection: why am I not as others are? Why was there a curse on my cradle? Why did I come into the world without any choice?', adding 'My art gives meaning to my life'. Thus he considered his entire work as a single entity: The Frieze of Life. The frieze was manifestly an expression of anxiety (for example, in The Scream) but also of tender pathos: of the 'dance of life'. (This seems to have been a common subject at the time; we find Gustav Mahler alluding to it in reference to the dance-like movements of his symphonies.) Munch perceived sex as an ineluctable destiny, and few of his works represent Woman (capitalized as usual) in a favorable light. In Puberty a skinny young girl meditates, sitting naked on her bed beneath the threatening form of her own shadow, while in The Voice a young woman, alone in the woods, attends to some inner whisper; these are the most sensitive representations of woman in Munch's work. In another iconic image, the Madonna, of which he painted various versions between 1893 and 1902, overtly offers her ecstatic sexuality and yet remains inaccessible. Why inaccessible? A lithographic version suggests the answer: around the frame which encloses the seductress the straggling spermatozoa wriggle in vain while, in the lower left-hand corner, a pathetic homunculus, a wizened and ageless wide-eyed fetus, lifts its supplicant gaze toward the goddess. Munch's lithograph verges on irony, to which he was not averse. Even so, modifying the well-known phrase, we may wish to suggest that 'irony is the courtesy of despair'. Munch's art represents women in the light of trauma. Seduction itself is a source of anxiety; satisfaction brings remorse (Ashes), and jealousy and separation are experienced as terrifying and depressing events. At

around forty-five, Munch suffered a profound depression and spent

eight months in a sanatorium in Denmark. Thereafter he gave up

the anxiety-laden subject matter so central to his work and began

painting everyday subjects with the same vigorous brushwork and

expressionistic colors as before. His motives may have been prophylactic.

He later claimed to a friend that he had simultaneously given up

women and alcohol, though here again irony is not ruled out. |

|

ART

BY EDVARD MUNCH ONLINE: ^top^

Ashes The Dance of Life Death in the Sickroom Evening on Karl Johan Madonna Model by the Wicker Chair Night in St. Cloud Puberty Red Creeper Self Portrait: Between Clock and Bed Self~Portrait with Burning Cigarette The Sick Child Starry Night Two Women on the Shore Vampire The Voice |